Andrew Sullivan, under the title String Theory and Miracles quotes part of a blog posting entitled One reason science is having trouble banishing religious thinking at the Democracy in America site (the original posting text is not there right now, may reappear) which notes that the spectacle of physicists widely promoting to the public the string theory multiverse is having the following effect:

It’s not always readily apparent to non-physicists why this kind of talk is less supernatural than a belief in the persistence of the soul after death….

But strictly in terms of how the argument between theists and atheists plays out in the public domain, there is a different quality to the tenets that are emerging on the atheistic, particle-physics side of things these days.

The string theory multiverse pseudo-science has done a huge amount of damage to the interests of string theory within the academic community, but it also threatens to do damage to the understanding and image of science among the public. Unfortunately, while there is more and more physics content in US popular media, it is often in the form of string theory-based pseudo-scientific nonsense rather than real science. For examples of this, see a new article in the Denver Post which catalogs some of this (while arguing that it’s a good thing):

TV is working through the shock of the age of terrorism and dismay at the broken boundaries of science, right before our eyes. Parallel universes? Bending time? Alternate dimensions? Some heavy-duty thoughts are seeping into prime time every week.

To the extent that TV reflects the culture at large, these shows seem to be saying we’re on the cusp of major change — technological, scientific, political or emotional. We may not have answers but we’re aware of expanding questions. In 2009, it has become accepted for folks on the couch to converse about the space-time continuum. Not that we understand string theory, but we recognize it when it pops up in TV scripts, peppering a spy thriller. “Lost” pushed the way with its dialogue about “moving the island,” leading fans to discuss time-shifting, wormholes and Einstein’s relativity theory.

Really.

The newer shows are picking up the string (theory) and running with it. There are hopeful signs in all this. The sci-fi series depict humans taking control of the planet, voting in favor of free will and standing up for the species. Maybe TV can provide some wishful thinking.

Whether or not, as H.G. Wells observed, a frightful queerness has come into life in general, it certainly seems to have come into scholarship and science. Once upon a time, it seemed that the humanities were pretty much lost for good, drowning in the incoherence and irrationality enthusiastically sponsored by postmodern crit-babble, the kind that was mercilessly dragged into the light by Alan Sokal in his famous expose of SOCIAL TEXT. But there was always the forward march of science to console yourself with… and now it turns out that that what purports to be the leading edge of fundamental physics is aggressively hyping ‘fashionable nonsense’, as Sokal’s 1997 book terms it—nonsense which is every bit as nonsensical as any of the deconstructionist gibberish that Sokal eviscerated more than a decade ago.

It’s implicit (and sometimes explicit) in Peter’s work, Lee Smolin’s work and that of other observers of the frightful queerness that is contemporary theoretical physics that this is the sort of trap science can fall into when it doesn’t have real data to bang its head against and make sense of, and maybe that’s enough to explain it. But the side-by-side train wrecks of scientific and literary/cultural theory suggests something more, some kind of intellectual nihilism that I find very, very depressing.

I don’t think it is scary if the general public grossly misunderstands some concepts from theoretical physics.

Think about Star Treck, since the invention of quantum mechanics and the multi-world interpretation there have

always been fantasies about travelling to a parallel universe. It is slightly annoying if someone at a cocktail party tries to explain the uncertainty principle to you because that special someone was enlighted by a Pherry Rhodan comic strip the he or she read in the morning paper. But neither scary or depressing.

You know what really scares me? A well known and established professor of theoretical physics publishes a scientific paper, claiming that an extra term in the Lagrangian in the path integral of the universe could explain why the LHC broke, and, after recovering from a fit of laughter I find that there are many intelligent people out there who did take this seriously (not believing it was true, of course, but believing that it was not meant as a joke).

You know what I’m talking about.

Tim vB,

I think the danger now is not that the public misunderstands what some prominent theorists are up to, but that they do understand it.

It is hard to stop all the silly speculation, because lack of evidence does not seem to discourage TV popularization or sci-fi plots. Of course there are a lot of ragged edges around quantum mechanics that really need to be worked on, but string theory does not appear to have made much progress in the quarter century or so since I first had it explained to me.

However, I do think there is merit to applying the same ways of thinking that have been effective for analyzing molecules to larger systems. This leads to a lot of unusual and nonsensical suggestions, but few people have the intuition to avoid the nonsense. It is not clear (to me, at least) that we fully understand why tools like Schrodinger’s equation have been so successful predicting chemical and electrical behavior. String theory may have been a distraction, but (as an engineer) my perception is that our understanding of quantum theory and it implications for larger systems is still at a very primitive stage of development. The viewing public is not really naive — they sense the confusion, and are drawn to it just like kids chasing a fire engine.

For most folks, even, say, a professional biochemist, the only basis for accepting the claims of high energy physicists is the authority mechanism – the claims are made by people with nice titles at respectable institutions, and there is some evidence (e.g. transistors) that claims made by similar people have translated into something tangible which would not have existed without those people. The professional biochemist, by projecting her own professional experience, is perhaps better situated than the `man on the street’ to judge which authorities should be trusted, but in the end it is a matter of picking one’s authority.

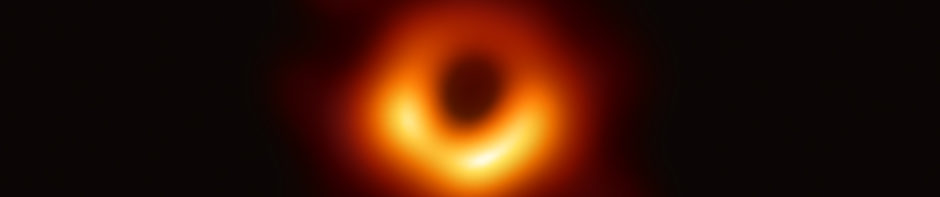

For many people, the people with fancy titles in elitist expensive institutions are inherently untrustworthy authorities – are not these essentially the same people who run the banks? – and something like the bible, or the minister expounding it, seems more accessible and more believable. Black holes can’t be seen with the naked eye anymore than can gods.

I certainly do think there is a basis for accepting certain authorities over others (transistors, h-bombs, genome sequencing, etc.. all attest to the superiority of certain paradigms), but I think also that the scientific community ignores the need to explain to world at large why its authorities should be considered credible, and dismisses too easily the credibility the world at large gives other authorities. Why should a man who can’t add fractions (most folks) listen to some nonsense about colored quarks?

You are absolutely right that quasi-religious pseudoscientific multiverses live in the same intellectual multiverse as do things like intelligent design, and they make far more difficult the task of communicating why scientific authorities should be trusted.

I love science fiction. It’s great entertainment and I see nothing wrong with it at all. I’m even willing to accept possible conclusions from science and math that can’t be tested with current technology. After all, when Einstein’s equations predicted the possibility of a gravitational collapse, he did not believe it really would exist in nature, much less someday be observed and studied from Earth. Even still, Einstein’s theories were based on sound observations about time and light, space and gravity. Then those theories were peer reviewed and verified by additional observations, many of which he proposed himself. This is the difference between science fiction and the scientific method. In my own humble opinion, a scientist should not propose a conjecture as fact without it being based on sound observation and without proposing a way that it could be falsified or verified.

This is the line between science fiction and the scientific method. When scientists cross that line, they may as well describe the universe the way my elders once did, by saying, “that’s just the way God made it”. Just to be clear, I have no problem with anyone who wishes to explain the cosmos that way, but it’s not science. Just as a particle can be both a wave and a solid bit of matter at the same time, I can allow for multiple explanations for the same thing.

My concern is that true science is not based on any sort of faith. It must be based on observations and include tests that can prove or falsify its predictions. This is an easy line to draw and many of today’s so-called scientists have morphed into nothing more than evangelists or science fiction writers. When Author C. Clark first proposed satellites, there was no science to back it up. It was a great idea, years before it’s time, but it was science fiction. If scientists want to write science fiction, that’s fine. Carl Sagan did a great job with “Contact”. But for goodness sakes, let’s not confuse a belief by faith, or science fiction, with the scientific method. If we do, science will lose all contact with reality and all those that call science nothing more than a popular paradigm will be justified in their accusation. In the end, scientists have a professional responsibility to separate science from religion and science fact from science fiction. I’m very disappointed in those scientists who fail in this professional responsibility.

“In the end, scientists have a professional responsibility to separate science from religion and science fact from science fiction. I’m very disappointed in those scientists who fail in this professional responsibility.”

I think it’s a bit trickier than that.

If you ask the physicists who go on about the multiverse and contact between alternate universes and so on about what they’re doing, they would probably tell you that they’re not doing science fiction, but exploring possibilities that are already within the scope of what they regard as ‘normal science’. The problem is that what’s regarded as normal science has changes significantly in the last thirty years or so. Once upon a time, normal science meant systematically extending the reach of one’s best hypotheses and analytic frameworks, those which had proven most sucessful to date, to novel problems suggested by new data, or an innovative take on old, previously unresolved problems, to yield a predictively satisfying result. You departed from this MO only when you weren’t getting anywhere and needed a *really* crazy alternative to standard models and concepts to make a breakthrough, and you didn’t regard that alternative as established until it had proven itself through further application. We all know from experience that most ideas that are just too god to be false wind up in the dustbin sooner or later. And the more drastically such ideas depart from the previous body of ‘battle-tested’ knowledge, the more likely they are to be discarded. You can count genuine paradigm shifts in physics on a proper subset of the fingers of one hand.

Something has changed that conception of normal science. The lack of new critical data allowing a push beyond the standard model—we’re stil sitting on tenterhooks waiting to see what the fate of the Higgs is!—combined with the incredible pressure, in the wake of electroweak unification, to finally finish the bloody job, cook up a successful TOE, and go home—seems to have led physicists to redefine normal science as a glass bead game with only the most indirect connection to any actual *facts*. Once your scientific culture changes in that direction, conflating thought experiments with real experiments, and possible worlds with the real world starts to become ‘normal’, and we get to… well, to where we are in the OP here.

And it’s not helped, of course, by the fact that some people feel that the right way to address string theory’s 10^500 vacuum states is to assert, completely seriously, that that outcome has ontological consequences which we must accept. Get all these factors interacting for long enough and the whole view of science that took us all these centuries to build up is in jeopardy…

BL, generally I believe we are in agreement. The question is what is science? What separates the fantastic thought experiments of Einstein from Star Trek fiction? What separates scientific fact from a belief through faith? Perhaps the question is even deeper as you suggest. If science hits a brick wall, is it acceptable to extend its reach with thought experiments that have no observational basis and mathematics that are the equivalent of proving that 0/0=every number?

In my own humble opinion, science is a profession. The pursuit of that profession is guided by the scientific method. Those who claim to be pursuing science, but do not use the scientific method are quacks. They may be well educated and well meaning quacks, but they are quacks nonetheless. I’m not saying that valuable insight cannot be gained by other methods, but rather that those methods are not science and anyone who claims to be doing science by other methods has lost their way along the path to scientific progress.

While I understand there is a great push to complete the job of unifying the fundamental forces, I do not agree that moving outside the scientific method is the correct course. It wouldn’t surprise me if it takes a very long time to collect the experimental data to complete this work. It could even be possible that the solution is many orders of magnitude more complex than anyone envisions, or that we may not be able to complete this work for many generations to come. In any case, the unification of the fundamental forces is not the only ongoing scientific work in physics. I do not believe that these attempts to go outside the scientific method are justified when considered in the balance of all the harm that fundamental science in all fields will suffer if scientists stray from the path of the scientific method.

That is of course, my own opinion. Others my feel it is justified to scrap the scientific method if there is any hope at all of solving this vexing problem. I don’t begrudge them their attempt at solving the problem, I only object to their calling themselves scientists. I really don’t know what to call them. Aspiring profits? Pseudo scientific evangelists? I don’t mean any disrespect by calling them quacks, but it’s the only term I know that applies to would-be scientists who have abandoned the scientific method.

If, in the end, the only solution to this problem depends on the assumption of something that can never be observed, then in my opinion it can be said that there is no scientific solution to the problem. There may be many problems that have no scientific answer, but that doesn’t justify throwing out the scientific method, since there are so many more problems that the scientific method can solve.

But I do not believe we should be willing to accept defeat this early in the game. I firmly believe that if all the time and money expended on trying to come up with pseudo scientific answers to the problem was dedicated to pursuing answers through the fundamental scientific method, the correct answer , if there is one, will be found much faster and with much less damage to other branches of real science. Perhaps we just need to be a little more patient and wait for the results to come out of the LHC over the next few years. Perhaps there is another experiment either here on earth or out in space that will point the way. But in any case, let’s not accept throwing out the method that gave us the transistor and the end of small pox, just to pursue a very remote possibility of advancing a few individuals careers.

It is said that we stand on the shoulders of scientific giants. So just how did they become giants? In every case it was through the rigorous application of the scientific method. I can’t think of a single scientific “giant” that became so by proposing solutions that can never be observed. Perhaps I need to adjust my thinking though and accept the existence of new pseudo scientific media and internet giants. I can accept that for entertainment purposes, as long as they quit claiming to be performing real science.

@GP:

“I’m not saying that valuable insight cannot be gained by other methods, but rather that those methods are not science and anyone who claims to be doing science by other methods has lost their way along the path to scientific progress…While I understand there is a great push to complete the job of unifying the fundamental forces, I do not agree that moving outside the scientific method is the correct course…. In any case, the unification of the fundamental forces is not the only ongoing scientific work in physics.”

Right, and that’s the crucial nub of the issue. What you’re saying here is an affirmation of the conduct of “normal science”, as it used to be understood, as the default strategy for obtaining hard, defensible conclusions—what used to be called *results*. But in high-energy physics, there is now quite a different ethic in place, where mathematical validations of highly abstract conjectures are seen as normal—regarded as just the latest avatar of what Dirac did with Clifford algebras way back when, and are themselves claimed to be results with *physical* content. Even more central is what you say about unification not being the only ongoing work (of importance) in science. Again, normal scientific practice in the past didn’t aim directly at such unification, which was rather an earned result based on patient accumulation of confirmations for progressively more general characterizations of physical phenomena. Plenty of impressive reputations were earned on the basis of normal science, and not a few Nobel Prizes (Hans Bethe comes to mind as a good case in point).

But that’s not the way things are seen within a sizable chunk of the professional physics community, apparently. A cash-strapped field with far more Ph.D.s than permanent (or even impermanent) jobs for them, a generation-old theoretical framework that no one seems to be able to take the next step from, operating in a general zeitgeist driven as much by celebrity as genuine earned authority, is almost certainly going to try to solve its problems by changing the rules of the game to play in the way that we’re talking about. In the case of Kaku & Co., the counter would almost certainly be, whatever increased people’s interest in science is good, and as you mentioned in the other thread, the program is clearly labelled ‘Sci-fi’. What worries me is that people may not recognize that not only the concepts (wormholes to other universes, time travel, etc.) but the ‘physics’ applied to those concepts on the program, are part of the ‘fiction’ in the ‘Sci-fi’ label….