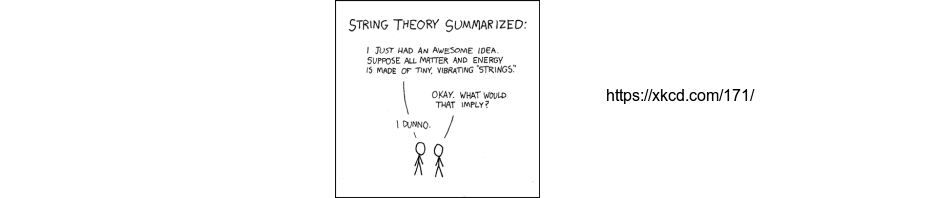

[Warning, somewhat of a rant follows, and it’s not very original. You might want to skip this one…]

In the last week or so, I’ve run into two critiques of the currently fashionable multiverse mania that take an unusual angle on the subject, raising the question of the “morality” of the subject. The first of these was from Lee Smolin, who was here in New York last week talking at the Rubin Museum. I probably won’t get this quite right, but from what I remember he said that discussions of a multiverse containing infinite numbers of copies of ourselves behaving slightly differently made him uneasy for moral reasons. The worry is that one might be led to stop caring that much about the implications of one’s actions. After all, whatever mistake you make, in some other infinite number of universes, you didn’t do it.

Over at Scientific American, yesterday they had John Horgan’s Is speculation in multiverses as immoral as speculation in subprime mortgages?. There’s more about this in a Bloggingheads conversation today with George Johnson, where Horgan describes his current reaction to multiverse mania as “I can’t stand this shit.”

I’m in agreement with Horgan there, but my own moral concerns about the issue are different than the ones he and Smolin describe. The morality of how people choose to live their everyday lives doesn’t seem to me to have much to do with whatever the global structure of the universe might be. The world we are rapidly approaching in which a multiverse is held up as an integral part of the modern scientific world view isn’t one in which many people are likely to behave differently than before, so I don’t share Smolin’s concerns. Horgan’s exasperation with seeing the multiverse heavily promoted by famous physicists appears to have more to do with the idea that this is a retreat by physicists from engagement with the real world, something morally obtuse in an era of growing problems that scientists could help address. For what he would like to see instead, I guess a good model would be John Baez’s recent decision to turn his talents towards real-world problems facing humanity, see his blog Azimuth for more about this. Personally, I’m not uncomfortable with the fact that many mathematicians and physicists find that they don’t feel they are likely to be of much help if they go to work on the technology and science surrounding social problems. Instead, one can reasonably decide that one has some hope of making progress on fundamental issues in mathematics or physics and choose to work on that instead. One can try and justify this by hoping that new breakthroughs will somehow, someday help humanity, although this may be wishful thinking. Or one can argue that working towards a better understanding of the universe is inherently worthwhile, so pursuing this while taking some care to avoid worsening one’s local corner of the world is a morally reasonable stance.

My own moral concerns about the multiverse have more to do with worry that pseudo-science is being heavily promoted to the public, leading to the danger that it will ultimately take over from science, first in the field of fundamental physics, then perhaps spreading to others. This concern is somewhat like the one that induced Alan Sokal to engage in his famous hoax. He felt that abandonment by prominent academics of the Enlightenment ideals exemplified by the scientific method threatens a move into a new Dark Ages, where power dominates over truth. Unfortunately, I don’t think that revelation of a hoax paper would have much effect in multiverse studies, where some of the literature has already moved beyond the point where parody is possible.

For a while I was trying to keep track of multiverse-promoting books, and writing denunciatory reviews here. They’ve been appearing regularly for quite a few years now, with increasing frequency. Some typical examples that come to mind are Kaku’s Parallel Worlds (2004), Susskind’s The Cosmic Landscape (2005), and Vilenkin’s Many Worlds in One (2006). Just the past year has seen Sean Carroll’s From Eternity to Here, John Gribbin’s In Search of the Multiverse, Hawking and Mlodinow’s The Grand Design, and Brian Greene’s new The Hidden Reality. In a couple weeks there will be Steven Manly’s Visions of the Multiverse. Accompanying the flood of books is a much larger number of magazine articles and TV programs.

Several months ago a masochistic publisher sent me a copy of Gribbin’s book hoping that I might give it some attention on the blog, but I didn’t have the heart to write anything. There’s nothing original in such books and thus nothing new to be said about why they are pseudo-science. The increasing number of them is just depressing and discouraging. More depressing still are the often laudatory reviews that these things are getting, often from prominent scientists who should know better. For a recent example, see Weinberg’s new review of Hawking/Mlodinow in the New York Review of Books.

While most of the physicists and mathematicians I talk to tend towards the Horgan “I can’t stand this shit” point of view on the multiverse, David Gross is about the only prominent theorist I can think of known to publicly take a similar stand. One of the lessons of superstring theory unification is that if a wrong idea is promoted for enough years, it gets into the textbooks and becomes part of the conventional wisdom about how the world works. This process is now well underway with multiverse pseudo-science, as some theorists who should know better choose to heavily promote it, and others abdicate their responsibility to fight pseudo-science as it gains traction in their field.

Cosmonut— No, 60 e-foldings is necessary for our observable region to have the correct properties, such as flatness, but the consequence is that it’s then a tiny patch of a far larger space. Think of what you have to do to a balloon to make a tiny surface patch look look very flat–you need to blow up the balloon to a size far more tremendous than that patch.

——————————————-

That’s what I used to think, but its not true.

60 (or maybe70) e-foldings are the minimum required to give a value of Omega of the *same order of magnitude* as 1.

So, for instance, if we had observed an Omega of 2 – that would indicate a (hyper)spherical universe of about the same size as the observable universe.

But even to explain *this*, we would need to either assume super fine-tuned initial conditions, or an inflation period with at least 60 to 70 e-foldings.

The idea is, that just after inflation ended, the observable horizon would indeed be a tiny patch of the whole universe. But then the horizon would expand until the size of horizon and universe became comparable.

(See Sean Carroll’s Spacetime and Geometry for the technical aspects of this.)

Now the point is, it is easy to get *more* than 60 e-foldings in the models, which would lead to the “small patch” effect you mention, even today.

But since we have no idea which model is right, nobody knows if we actually had just only a few more than 60, or billions of e-folds.

The number mentioned in articles is pretty arbitrary and varies widely.

@Marty:

Does an inflation-like era in the early universe imply an early de Sitter phase caused by one or more scalar fields tarrying for awhile (e.g. in a local minimum of the potential), or are there alternative pictures that can also yield something that looks like inflation and is fully consistent with all observations?

———————————–

There was an interesting post on this a few days back at Cosmic Variance.

http://blogs.discovermagazine.com/cosmicvariance/2011/02/07/do-you-think-inflation-probably-happened/

Sean makes the same point in the comments that while it is observationally clear that some kind of rapid expansion happened early on, we are not sure whether this corresponds to any inflation model currently around.

@Matt:

Hope I didn’t come across as condescending in my last reply. I think you may be a cosmologist yourself from the comments.

Its just that I got really interested in the question of how large our universe is compared to what we can observe.

I had initially thought that if inflation gives us 60 e-foldings, then maybe our universe is at least e^60 times larger than what we can see (a mind boggling thought !).

But then, from further readings, I came to the conclusion I just mentioned.

If you know of any lower bound to the size of our universe from observational evidence, I’d be very interested.

Just want to add my 25 cents… as a mathematician largely ignorant about real physics!…

Matt says (Feb 12):

“Some people go even a step further, and claim that the multiverse is an infinitely big space and that every conceivable (and inconceivable) possibility is realized there, with copies of you and me doing and living every possible way imaginable.

Now that’s entirely speculative, and we have no evidence to support…”

Of the multiverse ideas, this one seems to be the most completely problematic.

Yet to popular writers (and the general public) this is understandably the most attractive, as it can lead to all sorts of wonderful plots for sci-fi stories…There is NOTHING wrong with that, if it stays as sci-fi (it’s not just Sheldon, Leonard et al who draw inspiration from wild ideas-many of us got inspiration to study math or physics with well-written, creative sci-fi). I do object to real (ex?)-scientists blurring the distinction, es[ecially if they are using that to sell books, as that does a disservice to the endlessly honest and infinitely deep beauty of reality…

On to the “parallel copies of me” theory, obviously attractive to the ego in each of us…

Maybe this came about partly because of a confusion about the very successful and basic models in probability theory or dynamical systems. To be overly pedantic in the service of having something precise to address, thus an infinite sequence of tosses of a fair coin can be thought of as either a single sequence with certain statistical properties (a “sample path”) or as the space of all possible such sequences endowed with a probability measure. There is a standard way to pass from one to the other, due to Kolmogorov combined with the Ergodic Theorem. Ditto for Brownian motion. Additional clarity is added by realizing coin-tossing as the 2x(mod 1) map on the unit interval, with Lebesgue measure, coding points with their binary expansions. Then the infinite random choice of coin flips (made by “Tyche, the goddess of chance” in Billingsley’s beautiful explanation), is equivalent to a single random choice (by Tyche!) of a point in the interval, and the dynamics of the map moves us on to the next flip. But though this model is extremely useful, and though the space of all outcomes exists mathematically, no one thinks of all outcomes “actually” existing at the same time except mathematically.

On to the parallel multiverse. Now if in this universe I flip a coin infinitely many times, then presumably in the parallel universes all other sequences are realized, with a probability measure that reflects the Lebesgue measure. But then the

coin-toss model has been realized as a (very very small) factor (i.e. measure-preserving homomorphic image) of the multiverse!

In other words, the advocates of this particular multiverse fantasy have indeed made the mistake of conflating a successful mathematical idea with the “real world”. And this makes me question seriously their understanding of either. Here I have been talking only about extremely simple math ideas (which I do however know something about) and if there is that much confusion there, I hate to think how sloppy the thinking must be when the much more sophisticated math needed for partical physics or cosmology is involved….!!!

In short I second Peter’s concerns about the necessity and primacy of intellectual honesty. The real world is beautiful and amazing enough

without conflating and inflating it with lazy speculations; it is still wonderful to be able to say, “I don’t know!” And with that basis, we can honestly say “what if…!” and again begin to dream…

Peter,

I think the way you express yourself does do you favors. Science needs informed criticism to progress, and that criticism needs to be most vehement where there is the most hype.

I’m not qualified to evaluate technical issues in string theory, but I can imagine a biologist who submits a paper postulating that lions have sharp canines because there is a multiverse that includes universes with all possible biota, and we happen not to live in a dull-toothed lion universe. I don’t think that would pass peer review. Maybe we biologists are just too closed minded.

Don’t worry, you don’t sound at all like Motl. He has a Czech accent. And you’re FAR funnier than he is.

Well, ether (wrt speed of light) was accepted scientific fact for a long, long time. Likewise various forms of Lamarckism. Likewise Freudian nonsense. All well within the modern era; all had a long run. I guess the new thing with multiverses is the large body of scientists who know it’s shit, but don’t say so publicly.

Well, Eli could make a fair argument that the multiverse kills moral responsibility. If all choices are made, why bother thinking about consequences.

Lest you think such angel counting has no consequences, think about the revolutionary change brought in by the reformation with respect to moral responsibility.