Max Tegmark has a new book out, entitled Our Mathematical Universe, which is getting a lot of attention. I’ve written a review of the book for the Wall Street Journal, which is now available (although now behind a paywall, if not a subscriber, you can try here). There’s also an old blog posting here about the same ideas.

Tegmark’s career is a rather unusual story, mixing reputable science with an increasingly strong taste for grandiose nonsense. In this book he indulges his inner crank, describing in detail an uttery empty vision of the “ultimate nature of reality.” What’s perhaps most remarkable about the book is the respectful reception it seems to be getting, see reviews here, here, here and here. The Financial Times review credits Tegmark as the “academic celebrity” behind the turn of physics to the multiverse:

As recently as the 1990s, most scientists regarded the idea of multiple universes as wild speculation too far out on the fringe to be worth serious discussion. Indeed, in 1998, Max Tegmark, then an up-and-coming young cosmologist at Princeton, received an email from a senior colleague warning him off multiverse research: “Your crackpot papers are not helping you,” it said.

Needless to say, Tegmark persisted in exploring the multiverse as a window on “the ultimate nature of reality”, while making sure also to work on subjects in mainstream cosmology as camouflage for his real enthusiasm. Today multiple universes are scientifically respectable, thanks to the work of Tegmark as much as anyone. Now a physics professor at Massachusetts Institute of Technology, he presents his multiverse work to the public in Our Mathematical Universe.

The New Scientist is the comparative voice of reason, with the review there noting that “there does seem to be something a little questionable with this vast multiplication of multiverses”.

The book explains Tegmark’s categorization of multiverse scenarios in terms of “Level”, with Level I just lots of unobservable extensions of what we see, with the same physics, an uncontroversial notion. Level III is the “many-worlds” interpretation of quantum mechanics, which again sticks to our known laws of physics. Level II is where conventional notions of science get left behind, with different physics in other unobservable parts of the universe. This is what has become quite popular the past dozen years, as an excuse for the failure of string theory unification, and it’s what I rant about all too often here.

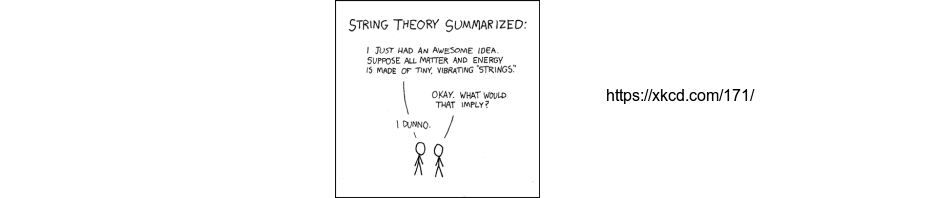

Tegmark’s innovation is to postulate a new, even more extravagant, “Level IV” multiverse. With the string landscape, you explain any observed physical law as a random solution of the equations of M-theory (whatever they might be…). Tegmark’s idea is to take the same non-explanation explanation, and apply it to explain the equations of M-theory. According to him, all mathematical structures exist, and the equations of M-theory or whatever else governs Level II are just some random mathematical structure, complicated enough to provide something for us to live in. Yes, this really is as spectacularly empty an idea as it seems. Tegmark likes to claim that it has the virtue of no free parameters.

In any multiverse-promoting book, one should look for the part where the author explains what their scenario implies about physics. At Level II, Susskind’s book The Cosmic Landscape could come up with only one bit of information in terms of predictions (the sign of the spatial curvature), and Steve Hsu soon argued that even that one bit isn’t there.

There’s only small part of Tegmark’s book that deals with the testability issue, the end of Chapter 12. His summary of Chapter 12 claims that he has shown:

The Mathematical Universe Hypothesis is in principle testable and falsifiable.

His claim about falsifiability seems to be based on last page of the chapter, about “The Mathematical Regularity Prediction” which is that:

physics research will uncover further mathematical regularities in nature.

This is a prediction not of the Level IV multiverse, but a “prediction” of the idea that our physical laws are based on mathematics. I suppose it’s conceivable that the LHC will discover that at scales above 1 TeV, the only way to understand what we find is not through laws described by mathematics, but, say, by the emotional states of the experimenters. In any case, this isn’t a prediction of Level IV.

On page 354 there is a paragraph explaining not a Level IV prediction, but the possibility of a Level IV prediction. The idea seems to be that if your Level II theory turns out to have the right properties, you might be able to claim that what you see is not just fine-tuned in the parameters of the Level II theory, but also fine-tuned in the space of all mathematical structures. I think an accurate way of characterizing this is that Tegmark is assuming something that has no reason to be true, then invoking something nonsensical (a measure on the space of all mathematical structures). He ends the argument and the paragraph though with:

In other words, while we currently lack direct observational support for the Level IV multiverse, it’s possible that we may get some in the future.

This is pretty much absurd, but in any case, note the standard linguistic trick here: what we’re missing is only “direct” observational support, implying that there’s plenty of “indirect” observational support for the Level IV multiverse.

The interesting question is why anyone would possibly take this seriously. Tegmark first came up with this in 1997, putting on the arXiv this preprint. In this interview, Tegmark explains how three journals rejected the paper, but with John Wheeler’s intervention he managed to get it published in a fourth (Annals of Physics, just before the period it published the (in)famous Bogdanov paper). He also explains that he was careful to do this just after he got a new postdoc (at the IAS), figuring that by the time he had to apply for another job, it would not be in prominent position on his CV.

One answer to the question is Tegmark’s talent as an impresario of physics and devotion to making a splash. Before publishing his first paper, he changed his name from Shapiro to Tegmark (his mother’s name), figuring that there were too many Shapiros in physics for him to get attention with that name, whereas “Tegmark” was much more unusual. In his book he describes his method for posting preprints on the arXiv, before he has finished writing them, with the timing set to get pole position on the day’s listing. Unfortunately there’s very little in the book about his biggest success in this area, getting the Templeton Foundation to give him and Anthony Aguirre nearly $9 million for a “Foundational Questions Institute” (FQXi). Having cash to distribute on this scale has something to do with why Tegmark’s multiverse ideas have gotten so much attention, and why some physicists are respectfully reviewing the book.

A very odd aspect of this whole story is that while Tegmark’s big claim is that Math=Physics, he seems to have little actual interest in mathematics and what it really is as an intellectual subject. There are no mathematicians among those thanked in the acknowledgements, and while “mathematical structures” are invoked in the book as the basis of everything, there’s little to no discussion of the mathematical structures that modern mathematicians find interesting (although the idea of “symmetries” gets a mention). A figure on page 320 gives a graph of mathematical structures which a commenter on mathoverflow calls “truly bizarre” (see here). Perhaps the explanation of all this is somehow Freudian, since Tegmark’s father is the mathematician Harold Shapiro.

The book ends with a plea for scientists to get organized to fight things like

fringe religious groups concerned that questioning their pseudo-scientific claims would erode their power.

and his proposal is that

To teach people what a scientific concept is and how a scientific lifestyle will improve their lives, we need to go about it scientifically: we need new science-advocacy organizations that use all the same scientific marketing and fund-raising tools as the anti-scientific coalition employ. We’ll need to use many of the tools that make scientists cringe, from ads and lobbying to focus groups that identify the most effective sound bites.

There’s an obvious problem here, since Tegmark’s idea of “what a scientific concept is” appears to be rather different than the one I think most scientists have, but he’s going to be the one leading the media campaign. As for the “scientific lifestyle”, this may be unfair, but while I was reading this section of the book my twitter feed was full of pictures from an FQXi-sponsored conference discussing Boltzmann brains and the like on a private resort beach on an island off Puerto Rico. Is that the “scientific lifestyle” Tegmark is referring to? Who really is the fringe group making pseudo-scientific claims here?

Multiverse mania goes way back, with Barrow and Tipler writing The Anthropic Cosmological Principle nearly 30 years ago. The string theory landscape has led to an explosion of promotional multiverse books over the past decade, for instance

- Parallel Worlds, Kaku 2004

- The cosmic landscape, Susskind, 2005

- Many worlds in one, Vilenkin, 2006

- The Goldilocks enigma, Davies, 2006

- In search of the Multiverse, Gribbin, 2009

- From eternity to here, Carroll, 2010

- The grand design, Hawking, 2010

- The hidden reality, Greene, 2011

- Edge of the universe, Halpern, 2012

Watching these come out, I’ve always wondered: where do they go from here? Tegmark is one sort of answer to that. Later this month, Columbia University Press will publish Worlds Without End: The Many Lives of the Multiverse, which at least is written by someone with the proper training for this (a theologian, Mary-Jane Rubenstein).

I’m still though left without an answer to the question of why the scientific community tolerates if not encourages all this. Why does Nature review this kind of thing favorably? Why does this book come with a blurb from Edward Witten? I’m mystified. One ray of hope is philosopher Massimo Pigliucci, whose blog entry about this is Mathematical Universe? I Ain’t Convinced.

For more from Tegmark, see this excerpt at Scientific American, an excerpt at Discover, and this video, this article and interview at Nautilus. There’s also this at Huffington Post, and a Facebook page.

After the Level IV multiverse, it’s hard to see where Tegmark can go next. Maybe the answer is his very new Consciousness as a State of Matter, discussed here. Taking a quick look at it, the math looks quite straightforward, his claims it has something to do with consciousness much less so. Based on my time spent with “Our Mathematical Universe”, I’ll leave this to others to look into…

Update: Scott Aaronson has a short comment here.