When I was in Edinburgh I picked up a copy of Graham Farmelo’s new biography of Dirac. It’s entitled The Strangest Man: The Hidden Life of Paul Dirac, Quantum Genius, and is not yet available in the US. I read the book on the plane trip back to New York and very much enjoyed it. While I’ve read a large number of treatments of the history and personalities involved in the birth of quantum mechanics, this one is definitely the best in terms of detail and insight into the remarkable character of Paul Dirac. I gather that Farmelo had access to many of Dirac’s personal papers, and he uses these well to provide a sensitive, in-depth portrait of a man who often is reduced to a bit of a caricature.

The book is less of a scientific biography than the other book about Dirac I know of, Helge Kragh’s 1990 Dirac, A Scientific Biography, and emphasizes more the development of Dirac’s personality and the story of his relations with others, especially with his father, his mother, and his wife (who was Wigner’s sister). I learned quite a lot about Dirac that I’d never known before, including for instance the story of his work on the atomic bomb project during WWII.

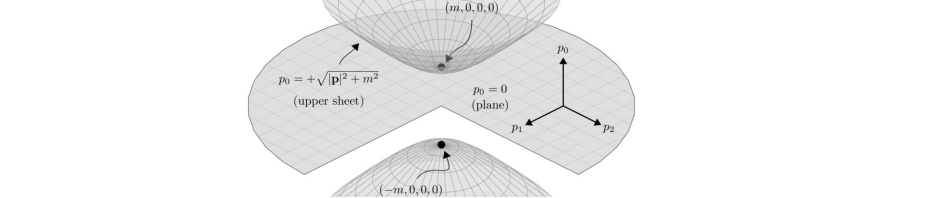

Dirac is responsible for several of the great breakthroughs in 20th century physics. At the age of 23, while still a graduate student, he took Heisenberg’s ideas and found the fundamental insight into what it means to “quantize” a classical mechanical system: functions on phase space become operators, with the Poisson bracket becoming the commutator. This remains at the basis of our understanding of quantum mechanics, and Dirac’s textbook on the subject remains a rigorously clear explanation of the fundamental ideas of quantum theory. Two years later he found the correct relativistic generalization of the Schrodinger equation, the Dirac equation, which to this day is at the basis of our modern understanding of particle physics. This equation also turns out to play a fundamental role in mathematics, linking analysis, geometry and topology through the Atiyah-Singer index theorem. Around the same time, Dirac was one of the people responsible for developing quantum field theory and quantum electrodynamics, as well as coming up with an understanding of the role of magnetic monopoles in electromagnetism.

The period of Dirac’s most impressive work was relatively short, ending around 1933. By 1937, the year he married, Farmelo reports Bohr’s reaction to reading Dirac’s latest paper (on the “large numbers hypothesis”):

Look what happens to people when they get married

Farmelo discusses a bit the question of why Dirac never later achieved the same sort of success after the dramatic initial period of his career. There may be a variety of reasons: the open problems got a lot more difficult, marriage and celebrity changed the way he lived and work, the war intervened, etc. For the rest of his career, Dirac took the attitude that there was something fundamentally wrong with QFT, and this may be why he stopped making fundamental contributions to it. He believed that a different sort of dynamics was needed, one that would get rid of the problems of infinities. He never was happy with renormalization, either in the form used to do calculations in QED after the war, or the more sophisticated modern point of view of Wilson and the renormalization group.

Unfortunately, some of the later parts of Farmelo’s book are marred by an attempt to enlist Dirac in the cause of string theory. This starts with the claim that Dirac’s work on “strings” during the fifties should be seen as a precursor of present-day string theory. These “strings” occur in the context of QED and magnetic monopoles, where they are unphysical artifacts of a choice of gauge, and have very little to do with the modern-day interest in physical strings as a basis for a unified theory.

Farmelo sees string theory as a resolution of the problem of infinities that Dirac would have approved of:

What would surely have impressed Dirac is that modern string theory has none of the infinities he abhorred.

I don’t see any reason at all to believe that Dirac would have been impressed with the idea of resolving the problems of QFT that bothered him by replacing it with a 10-dimensional theory that, despite the endless hype, has its own consistency problems (its perturbation expansion diverges, just like that of QFTs, and, unlike QFT, a 4d non-perturbative theory remains unknown). String theory was around for at least a dozen years before Dirac’s death, I’m sure he had heard about it, and there is no evidence he took any interest in the idea. Farmelo reports the reaction Pierre Ramond got from Dirac in 1983 when he tried to sell him on the idea of replacing 4d QFT with a higher-dimensional theory:

So he asked Dirac directly whether it would be a good idea to explore high-dimensional field theories, like the ones he had presented in his lecture. Ramond braced himself for a long pause, but Dirac shot back with an emphatic ‘No!’ and stared anxiously into the distance

The book ends with long discussion of Dirac and string theory that I think is seriously misguided, but it does include a mention of the fact that many physicists are unconvinced by the idea of string theory unification. Veltman is quoted, and the last footnote in the book refers the reader to Not Even Wrong.

Dirac is famous among physicists for his views on the importance of the criterion of mathematical beauty in fundamental physical law, once writing:

if one is working from the point of view of getting beauty in one’s equation, and if one has really sound insights, one is on a sure line of progress.

Farmelo believes that Dirac “would have revelled in the mathematical beauty” of string theory, but this is based on an uncritical acceptance of the hype surrounding the question of the “beauty” of string theory. “String theory” is a huge subject, and one can point to some mathematically beautiful discoveries associated with it, but the attempts to use it to unify physics have led not to anything at all beautiful, but instead to the landscape and its monstrously complex and ugly constructions of “string vacua” that are supposed to give the Standard Model at low energies.

I very much share Dirac’s belief that fundamental physics laws and mathematical beauty go hand in hand, seeing this as a lesson one learns both from history and from any sustained study of mathematics and physics and how the subjects are intertwined. As it become harder and harder to get experimental data relevant to the questions we want to answer, the guiding principle of pursuing mathematical beauty becomes more important. It’s quite unfortunate that this kind of pursuit is becoming discredited by string theory, with its claims of seeing “mathematical beauty” when what is really there is mathematical ugliness and scientific failure.

Ignoring the last few pages, Farmelo’s book is quite wonderful, by far the best thing written about Dirac as a person and scientist, and it’s likely to remain so for quite a while. Definitely a recommended read for anyone interested in the history of the subject, or some insight into the personality of one of the greatest physicists of all time.