This month’s American Scientist has a review entitled All Strung Out? of The Trouble With Physics and Not Even Wrong by prominent string theorist Joe Polchinski, and he has posted a slightly edited version of the review with some explanatory footnotes at Cosmic Variance. I assume there will be a lot of discussion of it over there, perhaps with Polchinski participating, so, even though I wanted to write some sort of response here, I’ll leave comments off and encourage people to discuss this over at CV.

First of all I should say that I was quite pleased to see Polchinski’s review. While I disagree with much of it, it’s a serious and reasonable response to the two books, the kind of response I was hoping that they would get, opening the possibility of a fruitful discussion. Unless I’ve missed something, the only review by a string theorist to appear in a publication so far has been Susskind’s almost purely ad hominem one in the Times Higher Education Supplement. There also are two other (not published in conventional media) reviews by string theorists that I know of, a serious one by Aaron Bergman, and a nutty one by Lubos Motl that Princeton University Press paid him to write for some mysterious reason. I’ve heard that several publications have had a hard time finding a string theorist willing to write a review of the books, which I guess is not too surprising. It’s not obviously a rewarding task to involve oneself in a controversy that has become highly contentious, and where some of the main points at issue involve very real and serious problems with the research program one has chosen to pursue.

Much of Polchinski’s review refers specifically to Smolin’s arguments; some of it deals with the endless debate over “background independence”, and the “emergent” nature of space-time in string theory vs. loop quantum gravity. I’ll leave that argument to others.

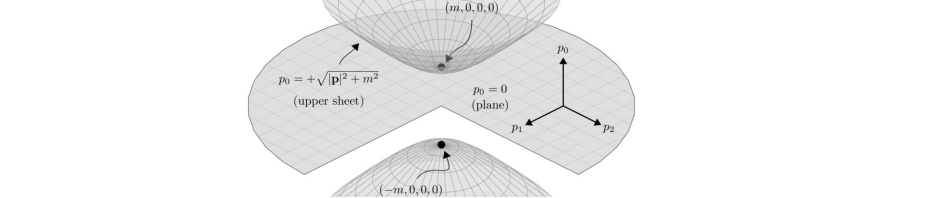

Polchinski notes that I make an important point out of the lack of a non-perturbative formulation of string theory and criticizes this, referring to the existence of non-perturbative definitions based on dualities in certain special backgrounds. The most well-known example of this is AdS/CFT, where it appears that one can simply define string theory in terms of the dual QFT. This gives a string theory with the wrong number of large space-time dimensions (5), and with all sorts of unphysical properties (e.g. exact supersymmetry). If it really works, you’ve got a precisely well-defined string theory, but one that has a low-energy limit completely different than the standard model in 4d that we want. This kind of string theory is well-worth investigating since it may be a useful tool in better understanding QCD, but it just does not and can not give the standard model. The claim of my book is not that string theories are not interesting or sometimes useful, just that they have failed in the main use for which they are being sold, as a unified theory of particle physics and gravity.

The lack of any progress towards this goal of a unified theory over the past 32 years (counting from the first proposal to use strings to do unification back in 1974) has led string theorists to come up with various dubious historical analogies to justify claiming that 32 years is not an unusual amount of time to investigate a theory and see if it is going to work. In this case Polchinski argues that it took about 50 years to get from the first formulation of QED to a potentially rigorous non-perturbative version of the theory (using lattice gauge theory). The problem with this analogy is of course that in QED non-perturbative effects are pretty much irrelevant, with perturbation theory describing precisely the physics you want to describe and can measure, whereas with string theory the perturbative theory doesn’t connect to the real world. When QED was first written down as a perturbative theory, the first-order terms agreed precisely with experimental results, and if anything like this were true of string theory, we wouldn’t be having this discussion. For the one theory where non-perturbative effects are important, QCD, the time lag between when people figured out what the right theory was, and when its non-perturbative formulation was written down, was just a few months (Wilson was lecturing on lattice gauge theory in the summer of 1973, having taken up the problem earlier in the year after the discovery of asymptotic freedom).

Polchinski agrees that the key problem for string theory is its inability to come up with predictions about physics at observable energies. He attributes this simply to the fact that the Planck energy is so large, but I think this is misleading. The source of the problem is not really difficulties in extrapolating from the Planck scale down to low energy, but in not even knowing what the theory at the Planck scale is supposed to be (back to that problem about non-perturbative string theory…).

Weinberg’s anthropic argument for the size of the cosmological constant is described by Polchinski as a possible “prediction” of string theory, and he recommends Susskind’s book as a good description of the latest views of string theorists. I’ve been far too rude to Polchinski in the past in expressing my views about this “anthropic landscape” philosophy, so I won’t go on about it here. He neglects to mention in his review that many of his most prominent colleagues in the string theory community are probably closer in their views on this subject to mine and Smolin’s than to his, and that our books are the only ones I know of that explain the extremely serious problems with the landscape philosophy.

Recently string theorists have taken to pointing to attempts to use AdS/CFT to say something about heavy-ion physics as a major success of string theory, and Polchinski also does this. I’m no expert on this subject, but those who are like Larry McLerran have recently been extremely publicly critical of claims like the one here that “Physicists have found that some of the properties of this plasma are better modeled (via duality) as a tiny black hole in a space with extra dimensions than as the predicted clump of elementary particles in the usual four dimensions of spacetime.” My impression is that many experts in this subject would take strong exception to the “better” in Polchinski’s claim.

Finally, about the “sociological” issues, Polchinski disagrees about their importance, believing they are less important than scientific judgments, but I’m pleased to see that he does to some extent acknowledge that there’s a serious question being raised that deserves discussion in the theoretical physics community: “This convergence on an unproven idea is remarkable. Again, it is worth taking a step back and reflecting on whether the net result is the best way to move science forward, and in particular whether young scientists are sufficiently encouraged to think about the big questions of science in new ways. These are important issues — and not simple ones.”

Again, my thanks to him for his serious and highly reasonable response to the two books.

I thought he treated you better than Lee. Apart from literary comments, and a couple of other hits, his focus on “predictions” was correct, but a conclusion that they are impossible seems a little over the top. Some of this other comments were fair, others were not. How’s your book doing anyway?

Just because it is not ad hominem does not mean it is a good review…and it is not…in the sense that a layperson reading it would get an incorrect view of the challenges faced by string theorists.

Polchinski makes little effort to be accurate and his bias is clear. For example, he incorrectly minimizes the lack of convergence (also mentioned by Penrose, incidentally) of the pertubative expansion. He mentions black holes as an application of string theory, when in fact these black holes are not ones we observe, and scarcely qualifies as an application as is normally understood by the meaning of the word.

I must say after reading this review, I unfortunately lost a certain amount of respect for Polchinski.

From my own experience with him I agree with the statement that Polchinski is a fair-enough person and surely one of the fastest thinkers available today (not necessarily implying an important role in furthering our understanding of fundamental physics). Since he likes to point out that there are nonperturbative formulations of superstring theory I think it would be reasonable to mention the resolution of the vacuum instability of perturbative bosonic string theory in the presence of D-branes (Sen’s work) which to my mind takes away a major motivation to introduce supersymmetry on the world sheet (just like the absence of a naive Higgs sector in the SM may forbid mention of a so-called gauge hierarchy problem).

As far as ADS/QCD as an ‘explanation’ for certain strong-interaction effects in heavy-ion collisions is concerned I am convinced that these claims are completely unfounded and dangerous because misleading.

“…which to my mind takes away a major motivation to introduce supersymmetry on the world sheet…”

Are you sure you know what you talk about? Susy on the world-sheet is needed to describe fermions, even in a theory that is not supersymmetric in space-time.

“As far as ADS/QCD as an ‘explanation’ for certain strong-interaction effects in heavy-ion collisions is concerned I am convinced that these claims are completely unfounded and dangerous because misleading.”

Is this conviction based on a similar deep understanding of the matters you attempt to judge here?

MoveOn, I believe I know exactly what I am talking about! I was talking about the vacuum instability of a purely bosonic string theory which seems to be cured in the presence of D branes. My personal feeling about fermions is that they are emerging phenomena in certain field theories (YM to be precise) and thus even as a concept should not enter into something soooooo fundamental as a string theory (be it supersymmetric or not in spacetime). I appreciate constructive remarks for one thing. On the other hand, I have developed a certain immunity against put-down attempts of hot-shot string educators.

Peter,

I am just curious; How many copies of your book have been sold until now?

R Hofmann: ” My personal feeling about fermions is that they are emerging phenomena in certain field theories”….

Well, if you can provide a model in which the fermions we observe, quarks and leptons that is, emerge from a YM theory, then surely many would appreciate it I do know that via the spin-from-isospin mechanism, fermionic excitations can occur in monopole backgrounds, do you mean something like that? But that hasn’t to my knowledge lead to anywhere. And in fact there had been ideas around a while ago where the superstring spectrum arises as some kind of solitons from the bosonic string. Also that AFAIK didn’t lead to anywhere.

For the time being, such speculations are much more far fetched than speculations about ordinary supersymmetric field and string theories. Same applies to your apparent disbelief in the HIggs mechanism (I think it was you who expressed that?). The moment you or someone else comes up with any remotely working “alternative” model, that would be great and hundreds would follow right away. But criticising string and/or susy field theories in a generic manner, in the sense “I don’t like any of that” for ideological or whatever personal feelings without having anything concrete in hands, is too cheap. Just saying “fermions should be emergent” is in my humble opinion not enough to constitute “constructive criticism”.

But constructve criticism is something I haven’t seen in this debate anyway. And that’s no surprise.

Not sure what happened here, thought I had turned off comments…

Still, I encourage people to discuss the Polchinski review over at CV. And stop the off-topic and un-enlightening sneering and hostility.

As for how the book is selling, I have only a vague idea, based on the Amazon rankings. As far as I can tell it’s doing better than the average book in this area, but is far from a best seller. In other words, somewhat better than Susskind’s, nowhere near Brian Greene’s. I’m quite happy that the book seems to be doing better than I expected, but, no, it’s not going to make me rich. Publishers report sales to authors I guess quarterly, with reports taking quite a long time to be prepared. So, at this point the only sales report I have is from the end of June in the UK, soon after the book went on sale.

MoveOn, ok let’s behave … Although Peter doesn’t like people being too explicit about their own brain childs at this location I sketch you hereby what I believe a lepton is. SU(2) Yang-Mills theory has a confining phase whose ground state is a condensate of paired, massless magnetic center-vortex loops. Excitations above this ground state are unpaired or twisted center-vortex loops, each selfintersection point constituting a Z2 charge of mass Lambda (the YM scale). If you want to read more about this I refer you to our papers. Peter, please don’t see this as an advertisement, its just answering MoveOn’s question. In the absence of any experimental evidence of susy but in the presence of anomalies in z pinch experiments, PVLAS, and CMB low multipoles I don’t quite see why you believe that admittedly speculative proposals of the kind sketched above are wilder than the MSSM for example.

Dear Ralf,

What you say about the bosonic string is not quite correct. Sen’s work has to do with open string tachyons, the closed string tachyon instability remains.

Michael

The practical reason why studying non-perturbative phenomena is important is that simple perturbative string models are not realistic. The fact that we now know the extreme non-perturbative limit and that it turned out to be dual to some other perturbative string (i.e. something unrealistic again) means no progress on the above crucial issue.

Actually, in many models of physics that explain the electroweak scale,

nonperturbative effects are thought to explain the ratio M_W/M_P which is

tiny. This is true in models where susy explains the higgs mass, for instance.

That has driven a lot of interest in studying nonperturbative phenomena.

It is simply not true that people study them only when perturbation theory

“seems to give the wrong answer”; often, as in the case of susy mentioned

above, one carefully looks for circumstances where an effect is

nonperturbative, in order to explain a small ratio in nature. Many such

dimensionless small ratios exist in our standard models.

Somewhat better than Susskind’s, nowhere near Brian Greene’s sounds like just the right spot.

huh?, I mean that string models in the weakly-coupled limit predict many non-existing massless moduli (e.g. dilaton gravity instead of gravity): a careful engineering work allows to (meta)stabilize all moduli, but this resulted in the infamous landscape. Years ago the hope was that non-perturbative effects could qualitatively improve the situation. However the present understanding of non-perturbative effects via strong/weak dualities means that in the opposite strong coupling limit one gets the same physics as in the weak coupling limit, and so again the same problems.

Well, “The Trouble with Physics” is in the list of “Best Books of 2006” in this week’s “Economist”. Here’s the list for the heading “Science and Technology”:

The Revenge of Gaia: Earth’s Climate Crisi and the Fate of Humanity. By James Lovelock.

The God Delusion. By Richard Dawkins.

The Omnivore’s Dilemma: A Natural History of Four Meals.

The Trouble With Physics: The Rise of String Theory, the Fall of Science, and What Comes Next. By Lee Smolin.

Not an uncontroversial book selection, I would say.

The edge.org in its last enquiry asked its correspondents to write a few lines about what they believe, but cannot prove. I believe, but cannot prove, that Ad/CFT with a dual QFT string definition will be found to be correct, but will need a redefinition of dimensions (4+1) and the realisation of a very heavy Higgs. Polchinski may be seeing a rather dim light at the end of a stringy tunnel…