Blogging has been light here, since little worthy of note in math/physics has been happening, and I’ve been busy with teaching, freaking out about the election, and trying to better understand Euclidean spinors. I’ll write soon about the Euclidean spinors, but couldn’t resist today making some comments about two things I’ve seen this week.

Sabine Hossenfelder yesterday had a blog entry/Youtube video entitled Particle Physicists Continue to Make Empty Promises, which properly takes exception to this quote:

A good example of a guaranteed result is dark matter. A proton collider operating at energies around 100 TeV will conclusively probe the existence of weakly interacting dark-matter particles of thermal origin. This will lead either to a sensational discovery or to an experimental exclusion that will profoundly influence both particle physics and astrophysics.

from a recent article by Fabiola Gianotti and Gian Francesco Giudice in Nature Physics. She correctly notes that

They guarantee to rule out some very specific hypotheses for dark matter that we have no reason to think are correct in the first place.

A 100 TeV collider can rule out certain kinds of higher-mass WIMPs, but it’s simply untrue that such an exclusion will “profoundly influence both particle physics and astrophysics.” Very few people think such a thing is likely since there’s no evidence for it and no well-motivated theory that predicts it.

Where I part company with Hossenfelder though is that I don’t see much wrong with the rest of the Gianotti/Giudice piece and don’t agree with her point of view that the big problem here is empty promises like this and plans for a new collider. Twenty years ago when I began writing Not Even Wrong, I started out by writing a chapter about the inherent physical limits that colliders were starting to hit, and the significance of this for the field. It was already clear that getting to higher proton energies than the LHC, or higher lepton energies than LEP was going to be very difficult and expensive. HEP experimentalists are now facing painful and hard choices about the future, which I wrote about in detail here under the title Should the Europeans Give Up?. The worldwide experimental HEP community is addressing the problem in a serious way, with the European Strategy Update one aspect, and the US now engaged in a similar Snowmass 2021 effort.

Many find it tempting to believe that the answer is simple: just redirect funds from collider physics to non-collider experiments. The problem is that there’s little evidence of promising but unfunded ideas for non-collider experiments. For the last decade there has been no new construction of high energy colliders, with as much money as ever available worldwide for HEP experiments. This should have been a golden age for those with non-collider ideas to propose. This continues to be the case: if you look at the European Strategy Update and Snowmass 2021 efforts, they have seriously focused on finding non-collider ideas to pursue. This should continue to be true, since I see no evidence anyone is going to decide to go ahead with a next generation collider and start spending money building it during the next few years. The bottom line result from the European process was not a decision to build a new collider, but a decision to keep studying the problem, then evaluate what to do in 2026. For the ongoing American process, as far as I know a new US collider is not even a possibility being discussed.

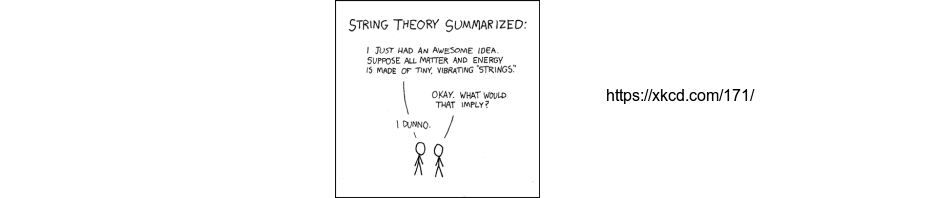

While HEP experiment is facing difficult times because of fundamental physical, engineering and economic limits, the problems of HEP theory are mostly self-inflicted. The decision nearly 40 years ago by a large fraction of the field to orient their research programs around bad ideas that don’t work (SUSY extensions of the Standard Model and string theory unification), then spend decades refusing to acknowledge failure is at the core of the sad state of the subject these days.

About the canniest and most influential HEP theorist around is Nima Arkani-Hamed, and a few days ago I watched an interview of him by Janna Levin. On the question of the justification for a new collider, he’s careful to state that the justification is mainly the study of the Higgs. He’s well aware that the failure of the “naturalness” arguments for weak-scale SUSY needs to be acknowledged and does so. He also is well aware that any attempt to argue this failure away by saying “we just need a higher energy collider” won’t pass the laugh test (and would bring Hossenfelder and others down on him like a ton of bricks…).

The most disturbing aspect of the interview is that Levin devotes a lot of time (and computer graphics) to getting Arkani-Hamed to explain his 1998 ideas about “large extra dimensions”, repeatedly telling the audience that he has been given a \$3 million prize for them. This paper has by now been cited over 6300 times, and the multi-million dollar business is correct, with the prize citation explaining:

Nima Arkani-Hamed has proposed a number of possible approaches to this [hierarchy problem] paradox, from the theory of large extra dimensions, where the strength of gravity is diluted by leaking into higher dimensions, to “split supersymmetry,” motivated by the possibility of an enormous diversity of long-distance solutions to string theory.

At the time it was pretty strange that a \$3 million dollar prize was being given for ideas that weren’t working out. It’s truly bizarre though that Levin would now want to make such failed ideas the centerpiece of a presentation to the public, misleading people about their status. The website for the interview also promotes Arkani-Hamed purely in terms of his failures, presented as successes:

Nima Arkani-Hamed is one of the leading particle physics phenomenologists of the generation. He is concerned with the relation between theory and experiment. His research has shown how the extreme weakness of gravity, relative to other forces of nature, might be explained by the existence of extra dimensions of space, and how the structure of comparatively low-energy physics is constrained within the context of string theory. He has taken a lead in proposing new physical theories that can be tested at the Large Hadron Collider at CERN in Switzerland,

This is part of the overall weird situation of the failed ideas (SUSY/strings) of 40 years ago: they still live on in a dominant position when the subject is presented to the public.

At the same time, the topics Arkani-Hamed is working on now are ones I think are more promising than most of the rest of what is going on in HEP theory. The interview began with a discussion of Penrose’s recent Nobel Prize, with Arkani-Hamed explaining Penrose’s fantastic insights about twistor geometry and noting that his own current work involves a fundamental role for twistor space (personally I see some other promising directions for using twistor geometry, more to come about this here in the future).

In contrast to Hossenfelder, what I’m seeing these days in HEP physics is not a lot of empty promises (which were a dominant aspect of HEP theory for several decades). Instead, on the experimental side, there’s an honest struggle with implacable difficulties. On the theory side increasingly people have just given up, deciding that it’s better to let the subject die chained to a host of \$3 million prizes for dead ideas than to honestly face up to what has happened.

Update:

In case anyone needs any reminder of how bad the propaganda problem is:

https://kids.kiddle.co/String_theory

It appears this kind of thing is driven by a propaganda problem on Wikipedia.